When COVID-19 Hit, Education Research Changed

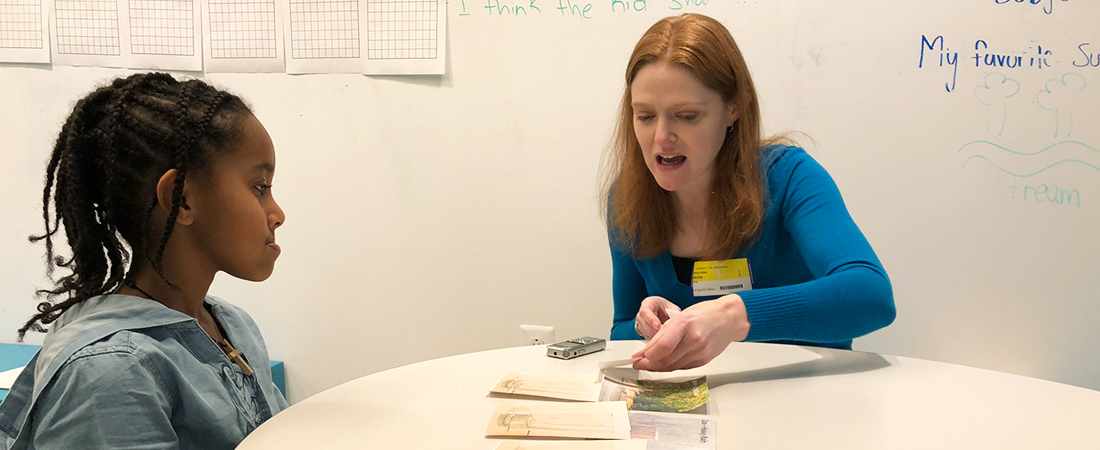

Before schools closed, researchers worked face-to-face with students on the Streams of Data project.

At the beginning of March, EDC’s Joy Kennedy was planning trips to four cities to recruit families for a new study on early literacy. She and her research team had already enlisted 127 families in Phoenix, Arizona, and Birmingham, Alabama, and they wanted to wrap up recruitment by the end of the month.

But as Kennedy watched news reports detailing increasing totals of coronavirus cases around the United States, she became worried. Was it safe for her or her team to travel? Soon, she had to make a decision that would significantly impact whether her research went ahead as planned—or not.

“I wound up pausing those trips,” she says. “The last thing I wanted this study to be in the news for was spreading COVID-19 to six different hubs.”

Kennedy is not alone in having her research disrupted by the coronavirus outbreak. With the pandemic leading to drastic changes in daily life, EDC researchers have had to find new ways to connect with study participants to continue their work. While that has been a challenging process for many, the experience has also broadened their notions of how to conduct high-quality education research in virtual settings.

“If we can figure out how to do virtual interviewing successfully, it might serve as template for other ongoing research projects,” says Randy Kochevar, director of EDC’s Oceans of Data Institute.

Kochevar is currently leading an investigation of how elementary school students interpret data from maps and graphs. Before the pandemic hit, he was planning to send a research team to Virginia and Maryland to conduct face-to-face interviews with students. When that became impossible, the team decided to move the data collection to Google Meet.

This switch had implications for the research. A new research consent form allowing researchers to record their interactions with participants had to be created and signed. The team also had to figure out how to collect non-verbal data in a virtual setting, which meant redoing their research protocols.

“The hardest part was figuring out the tech so that we could capture the kids’ gestures as they were mousing around the screen, while the researcher still controls the image the kid sees,” says Kochevar.

For her part, Kennedy decided to split her research evaluating the impact of digital media from the PBS program Molly of Denali on young children’s literacy development into two distinct studies. The first includes the families who had enrolled before she cancelled her trips in March; the second will be an all-virtual study with new families that will begin later this summer.

But this decision came with significant concerns. To close out the first study, the research team would have to collect outcome data from the 127 study participants virtually, not face-to-face as originally planned. Then there was the issue of how to replicate the researcher-family interactions in a virtual environment. The team turned to Zoom, both because families were familiar with it and because of its “breakout room” feature, which enabled them to recreate to some degree the experience of meeting with researchers in person.

“If this pandemic has shown us anything, it’s that research is not going to go ahead as normal for a while,” says Kennedy. “We need to be agile and to think through a lot of these methodological issues to do remote data collection.”

Equity in the balance

However, the transition to conducting research virtually has introduced another variable into academic studies: inconsistent access to technology, including the Internet, among study participants. Alan Stockdale, director of human protections at EDC, says that this has real implications for research.

“When you move research online, you may be excluding the 20 or 30 percent of people who do not have access to broadband internet at home,” he says. “These individuals are more likely to be part of disadvantaged populations or live in rural communities, which a lot of our research is focused on.”

For example, Kochevar’s team recommended that students use a laptop or tablet to participate in the Google Meet sessions with them. Some students, however, joined using their mobile phones—whose smaller screen size makes it more difficult for researchers to gather data on students’ gestures.

Kennedy’s study provided a data-enabled tablet to every family, but high-speed Internet access is still a concern, especially in urban and rural communities. When Zoom interviews are interrupted by dropped signals, there isn’t much her research team can do but try to reconnect.

“There’s no way to do this research if you don’t have a strong, reliable Internet connection,” she says. “There are ways we might be excluding families who are our main focus.”

Still, Kennedy has become a bit of a convert on the issue of conducting research remotely. Before the pandemic, she thought it was too difficult to keep young children engaged over video chat, and that the technical issues were too daunting. But now that she has been able to do it, she sees virtual research as potentially granting her access to new communities across the country.

“The more we do this, the more feasible it is,” she says. “We have decades of research about how to do research in person. Now we have to figure out how to do it online.”