Assessing the Global Effects of COVID-19

It’s easy to say that the COVID-19 pandemic has changed everything. But by how much?

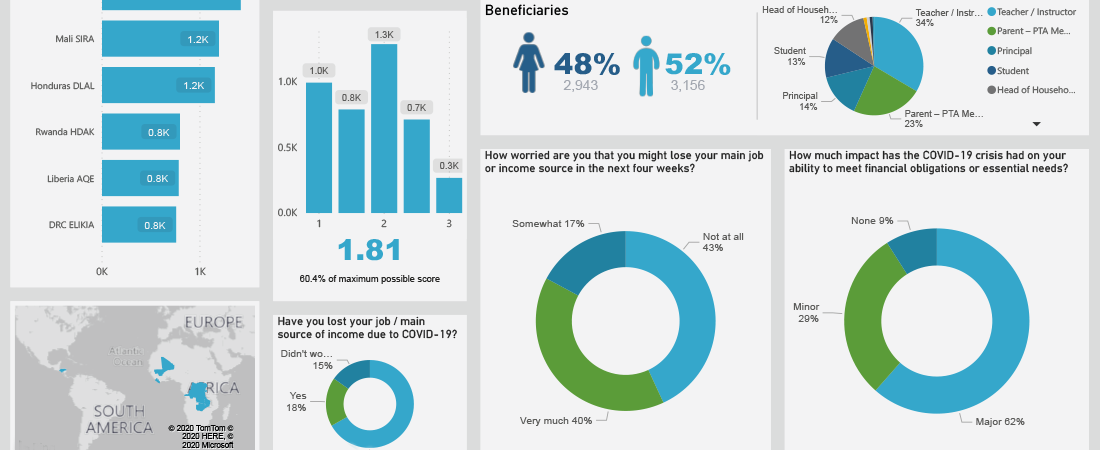

Since May, EDC researchers have been surveying teachers, parents, education officials, and youth across Honduras, Zambia, Rwanda, Mali, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Survey questions focus on how the pandemic has affected their health, livelihoods, educational opportunities, and frame of mind. To date, more than 6,500 surveys have been administered.

The results are creating a picture of the pandemic’s human effects. Among the findings:

- 83% of respondents report being very concerned about their own health or the health of members of their household.

- 64% report having less access to food than before the pandemic.

- 65% report that their children are accessing replacement educational activities in the wake of school closures.

The full data reveal that the pandemic has impacted communities in vastly different ways. However, in nearly all contexts, people who were already on the margins are now worse off than before, says Lisa Hartenberger-Toby, who leads EDC’s International Monitoring, Evaluation and Research team.

“This [pandemic] has exacerbated some of the inequities that already existed, and we can really see that in the data,” Hartenberger-Toby says.

As evidence, Hartenberger-Toby points to the survey findings about employment. While only 17 percent of total respondents indicated that they had lost their job due to the pandemic, rates differed widely across different contexts. For example:

- Only 5% of educators surveyed reported losing their jobs.

- In Rwanda alone, 56% of youth reported having lost their main source of income.

Disparities also showed up in access to education, as seen in data from Zambia:

- 60% of students in government schools had access to replacement educational activities.

- Only 42% of students in community schools—typically poorer, parent-organized institutions—had access to such activities.

“The data allow us to pinpoint who has access to education, who has job security, and who doesn’t,” Hartenberger-Toby says. And the data paint a clear picture of what is going on. “If you are a civil servant in these countries, you are doing ok. If you are a youth, you aren’t.”

Improving Programs

The survey is also being used to gather country-specific data, which will shape EDC’s educational and economic programs, says Neena Aggarwal, a research assistant who is coordinating the data collection.

“These data allow projects to respond more effectively in the context of a changing pandemic,” Aggarwal says. “Knowing in what ways beneficiaries are affected, such as their access to food or their level of trust in health messaging, can help project staff better support participants’ needs.”

In Mali, for example, participants are asked whether they have been listening to the educational lessons that the government began broadcasting over the radio in the spring. The data revealed that many families were not. So EDC’s USAID-funded Mali SIRA project produced a new radio announcement reminding parents to tune in. The announcement also told parents how they could use those lessons to support their children’s learning while at home. Since the launch of the radio spots, the data show that listenership to the educational lessons has risen from 28% of families surveyed to 37%.

In Liberia, home to EDC’s USAID-funded Accelerated Quality Education for Liberian Children (AQE) program, the data revealed that parents were three times as likely to say they wanted schools to implement robust handwashing measures than either masking or physical distancing protocols ahead of the fall school reopening. EDC’s Apollo Nkwake attributes this discrepancy to parents’ experiences during the 2015 Ebola epidemic, when handwashing was emphasized, but masking and physical distancing were not part of daily prevention measures.

“These data are helping us recognize that we have a lot of people in the communities who don’t realize that COVID-19 is different than Ebola,” says Nkwake. “Yes, we have to do the handwashing. But we also have to do the masks, and parents aren’t worried about that.”

As a result of this finding, Nkwake and AQE staff are now adapting their school-based prevention activities to prioritize the need for masks and physical distancing—in addition to handwashing—to stem the spread of the coronavirus.

These programmatic changes would likely not have occurred without this data collection effort, says Hartenberger-Toby. She notes that EDC plans to continue the survey to evaluate the impact of school re-openings and government policy changes in the six countries.

“We want to gather a broad understanding of the impact of this moment, so that we can think through what it means for people and for our projects,” Hartenberger-Toby says. “We’re discovering a lot of things that we just didn’t know.”